|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Real Estate

| |

|

|

Design Perspectives By Clair Enlow |

April 21, 2004

Design Perspectives: Are we better off without the viaduct?

Special to the Journal

Three years ago, the Nisqually quake threatened to do what Seattle citizens could not seem to accomplish on their own -- take down the Alaskan Way Viaduct. The event released a groundswell of creative energy on the waterfront. It is still building.

In February, 300 people from five countries labored for two days over concepts for a rediscovered, post-viaduct waterfront. The event, sponsored by CityDesign, was declared the largest organized design charrette ever held in Seattle.

Design professionals, students and citizens were assembled into 22 teams, and donated their time to re-imagining the waterfront. Their visions include new neighborhoods, green promenades, tiers of mixed-use buildings on the upland slopes, outdoor theaters and viewing towers. There are new peninsulas and islands, shallow water terraces, tidal basins and eel grass platforms for salmon.

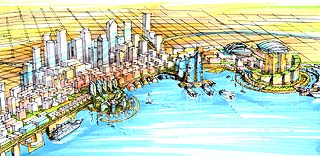

Images courtesy of CityDesign

Envisioning a waterfront that was active around the clock, Team 11 created several new neighborhoods along the water's edge that would serve as signature elements on the city's skyline. The team is composed primarily of people from the firm Busby Perkins & Will, with Peter Hockaday as facilitator.

|

In these dreams, the viaduct is gone. State Route 99 is swept underground, out of sight and out of mind, without the roaring traffic that now clatters over Alaskan Way. Taxpayers and government would have to come up with the billions needed to sink the highway and cover it up.

In the meantime, state legislators are doing their best to make sure the dreamers and designers don't get ahead of the traffic -- that is, the 110,000-plus vehicles per day now moving through the corridor that is Seattle's waterfront. To make their point, they attached a proviso to this year's $177 million funding package for project planning. It states that none of the money can be used toward any plan that would reduce capacity along SR-99.

The message is clear. Choose from the following: rebuild an aerial highway, build a tunnel or pave most of the 335 acres of land pictured in the sketches that have been pouring out of workshops and charrettes for months. The five options now included in the draft environmental impact statement released this month by Washington State Department of Transportation, the city and the Federal Highway Administration are all variations on one of these three scenarios.

Technically, the six-lane "surface" alternative, which would give us six lanes along Alaskan Way, is in violation of the no-reduction-in-capacity proviso, which was issued after the alternatives were set. And even with reduced capacity for vehicles and freight, it's no picnic for waterfront enthusiasts. The place is still dominated by cars and pavement.

What's wrong with this picture?

Before the decision to bury the highway is made and the funding is found, the viaduct might shake again. At the very least, the creative energy might crash. What's more likely is that planners and dreamers may be on a collision course with political and economic reality.

The reality is that no government or public agency -- not the city of Seattle, not the Puget Sound Regional Council and certainly not the Washington State Department of Transportation -- has been willing to question the need to sustain capacity along the SR-99 corridor.

But the possibility that traffic along an established route can be reduced must be considered. Otherwise, we must prepare to resign ourselves to a waterfront fate that was determined during the Eisenhower era and is sustained by a state bureaucracy and politicians from far away counties.

Encouraged by maverick transportation planners like Ralph Cipriano, formerly of the Puget Sound Regional Council, The People's Waterfront Coalition (www.peopleswaterfront.org) has challenged the capacity assumption.

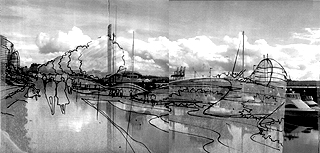

Several elements emerged from recent waterfront design charrettes such as connections to Pike Place Market and the University Street cultural corridor. There are terraced, park-like open spaces, connected by monorail, water taxis, streetcars and tramways.

|

Last week the group unveiled its agenda: don't replace the highway. They say the public should demand that the final EIS for the Alaskan Way Viaduct project include a no-replace alternative.

The coalition is led by Cary Moon, principal of Landscape Agents, an urban design and landscape design firm; Julie Parrett, a landscape and urban designer; and Grant Cogswell, co-author of the Seattle Monorail Initiative. Moon and Parrett led a team to develop a waterfront planning and design proposal for Allied Arts of Seattle's Waterfront Collaborative last fall.

What belongs on Seattle's waterfront, they say, is open space and commerce. Planning should be guided by access, environmental stewardship and creation of a multi-use, multi-faceted, urban waterfront that's connected to the rest of the city.

What's wrong, according to Moon, is no one has really addressed alternatives to replacing SR 99. About 60 percent of traffic on the viaduct would have to find another way through or around downtown Seattle. For the rest, destined for downtown, there are a number of alternate routes. In a WSDOT study, 40 percent of viaduct users would not pay a $1 toll to use it.

We've already had a taste of life without the viaduct, when it was out of commission following the quake. Even after it reopened, trips were down 40 percent and have built back up slowly.

There is a lot of extra capacity in Seattle's street grid, if we could just capture it, said Moon. According to her group's Web site, a rebuilt four-lane Alaskan Way, connected to the city street grid, could accept another 10,000 trips a day. Another 40,000 to 60,000 more would be absorbed by a reorganized Interstate 5, underused regional arterials like Airport Way, one-way couplets and signal timing, dedicated freight lanes, reconstructed choke points at both ends of downtown, and other measures.

In fact, Seattle's Department of Transportation is working on finding ways to tune the city's street grid so that it can accept traffic that would be displaced after sudden failure of the viaduct or during the years it would take to construct an alternative. There are 21 discrete traffic fixes in the plan, due this spring. Moon points out that the success of this effort, called the Central City Access Strategy, begs the question: do we need a freeway?

Even if all of these fixes are found, and made, it will probably be less expensive than a tunnel -- and far less disruptive. But there will still be a gap between the supply of pavement and the demand for faster trips in urban Puget Sound. So where does that leave the decision-making process? The choice to say "no" is still there -- for cities and for individuals.

According to the The People's Waterfront Coalition, people move their residence or workplace every three years, on average. Each occasion is an opportunity to live closer to work -- or to mass transit. If taxpayers don't continue to sponsor a quick commute along the waterfront, more people may take advantage of other opportunities.

Charles Anderson, landscape architect for the Olympic Sculpture Park, got involved in the recent waterfront charrette.

|

Consider some alternatives. To make their point about the prohibitive expense of a tunnel, the coalition has some favorite facts. For the same price, they say, we could: buy 10,000 helicopters and fly freight and commuters downtown. Build six more pairs of stadiums. Write every viaduct commuter a check for $50,000.

Quite aside from the necessary reconstruction of the seawall along Elliott Bay, any tunnel alternative would have to be classified as a megaproject. And the costs of megaprojects are notoriously underestimated and over budget.

A study published by Cambridge University Press this year argues that the costs of massive bridge and tunnel projects all over the world are systematically underestimated and the benefits overestimated. The reasons are as complex as the huge public and private partnerships needed to produce them, says the summary. But in selling these projects to the public, the real risks are simply never explicitly addressed.

Even if the money were there, said Moon, "You don't buy something you don't need just because you know where the money is coming from."

Now that cities have started counting the real costs to development and quality of life, and now that 30- and 40-year-old freeways are nearing obsolescence, a growing number of cities are exercising their political prerogatives to say no to construction or replacement. Think of Portland, where they dismantled a highway along the waterfront in the mid-70s. And San Francisco, where the heavily used Embarcadero Freeway that crumpled in the 1989 earthquake, was simply taken down. No crisis has ensued, and these cities have proudly embraced their respective waterfronts.

On the other hand, think of Boston, which opted to put its downtown freeway -- a vital link in an interstate highway system -- underground. At around $18 billion, the cost of the Big Dig is now triple the cost of original estimates, and counting.

Photo by Clair Enlow

Cary Moon of The People's Waterfront Coalition wants a no-replace alternative studied as part of the Alaskan Way viaduct replacement project.

|

This is a good time to review the lessons of the last 50 years, since the viaduct was built. Freeways give us vastly increased mobility between and through our cities. But they show contempt for the cities themselves, slicing through old neighborhoods and open spaces with concrete and noise.

They were successful in closing the vast distances of the American landscape. But a successful city is a destination and also a good place for many to live. Square footage is dear -- or should be. And every square foot of Seattle waterfront counts. At the very least, all the dreams and sketches and hard work of hundreds of volunteers should show us that.

The comment period for the draft environmental impact statement on alternatives for the replacement of SR 99 ends June 1. (Access the draft EIS at city libraries or at WSDOT's Web site, www.wsdot.wa.gov/projects/viaduct/comm_center.htm.

Clair Enlow can be reached by e-mail at clair@clairenlow.com.

Previous columns:

- Design Perspectives: Expectations bloom in Seattle this spring, 03-24-2004

- Design Perspectives: Are we doomed to lose a Fifth Avenue gem?, 02-25-2004

- Design Perspectives: Monorail and Seattle Center: date with destiny?, 02-04-2004

- Design Perspectives: A look at the Design Commission's first 35 years, 12-24-2003

- Bold strokes will lead us back to the bay, 11-26-2003

- Time for design in Portland's architecture-free zone, 10-22-2003

- DCLU pares down name, bulks up mission, 09-17-2003

- City re-thinks its vision for Civic Center open space, 08-20-2003